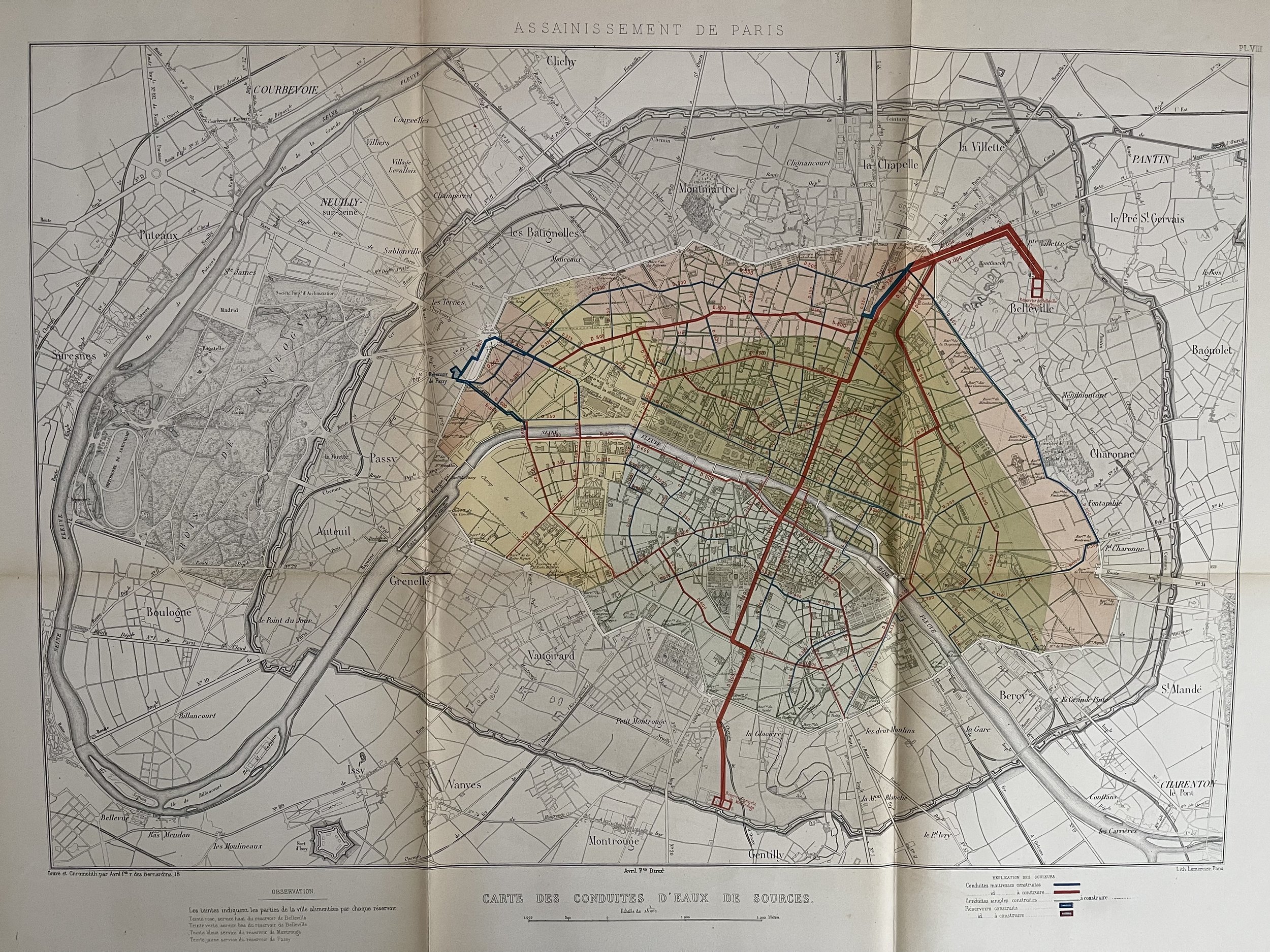

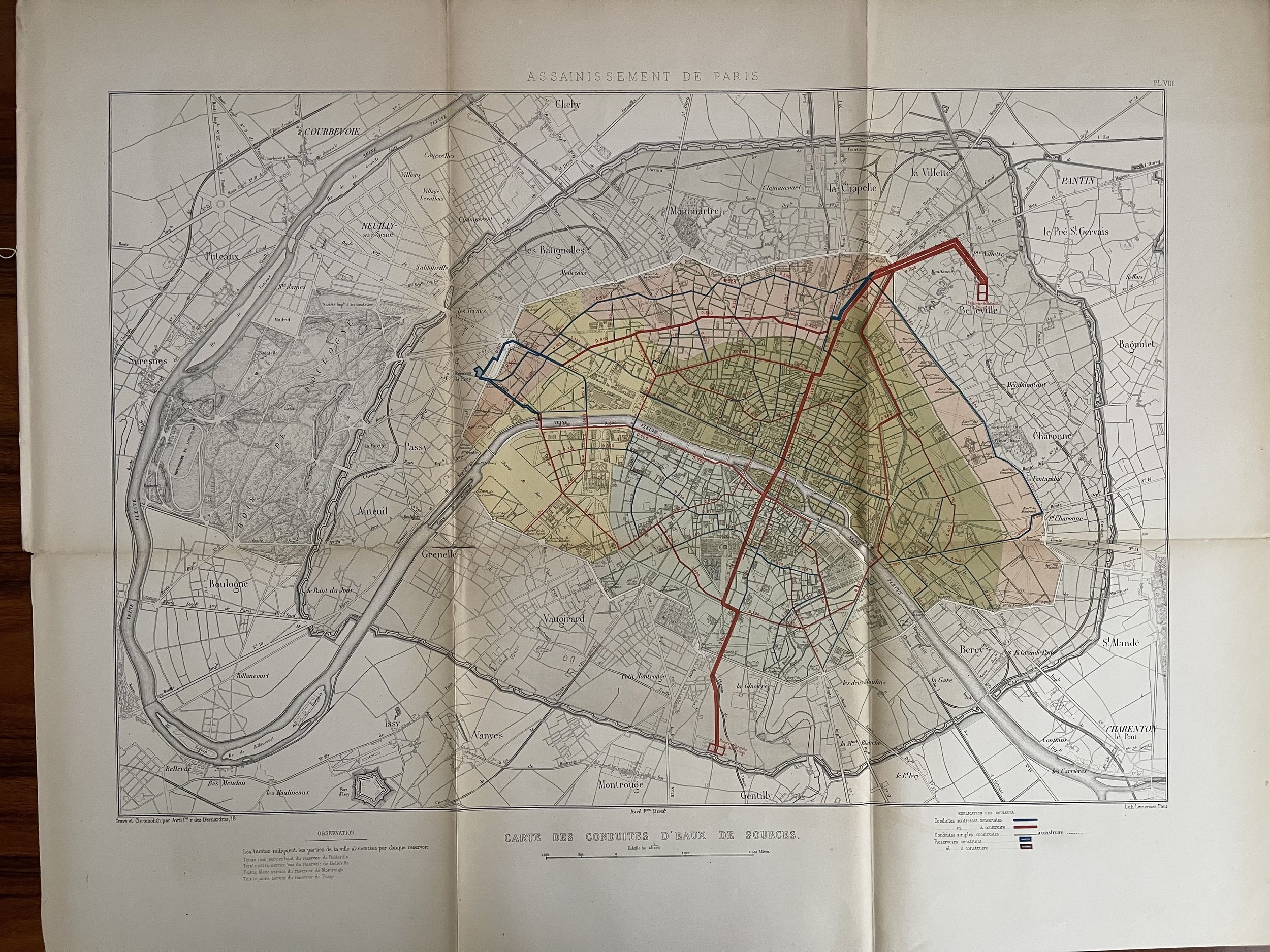

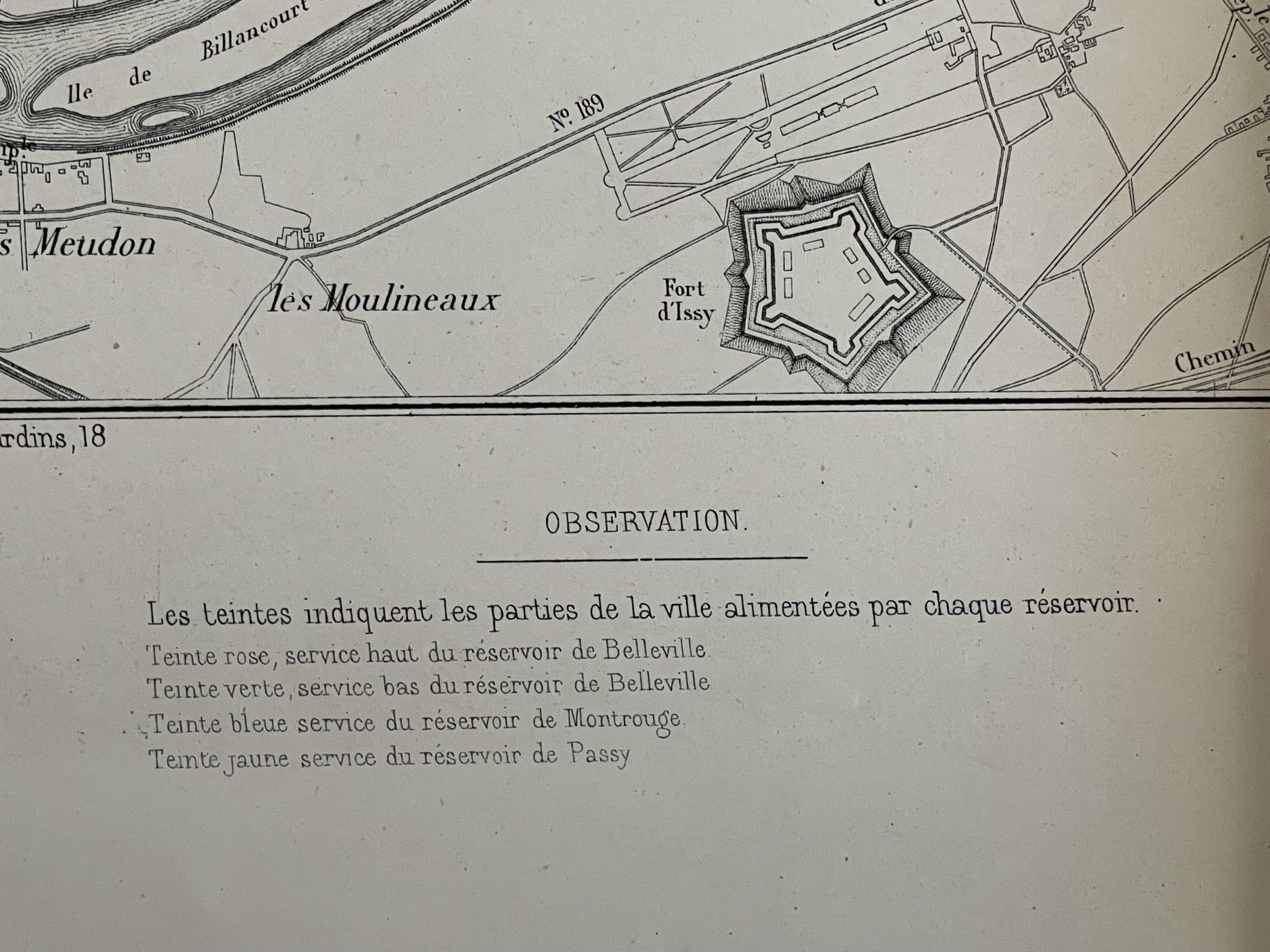

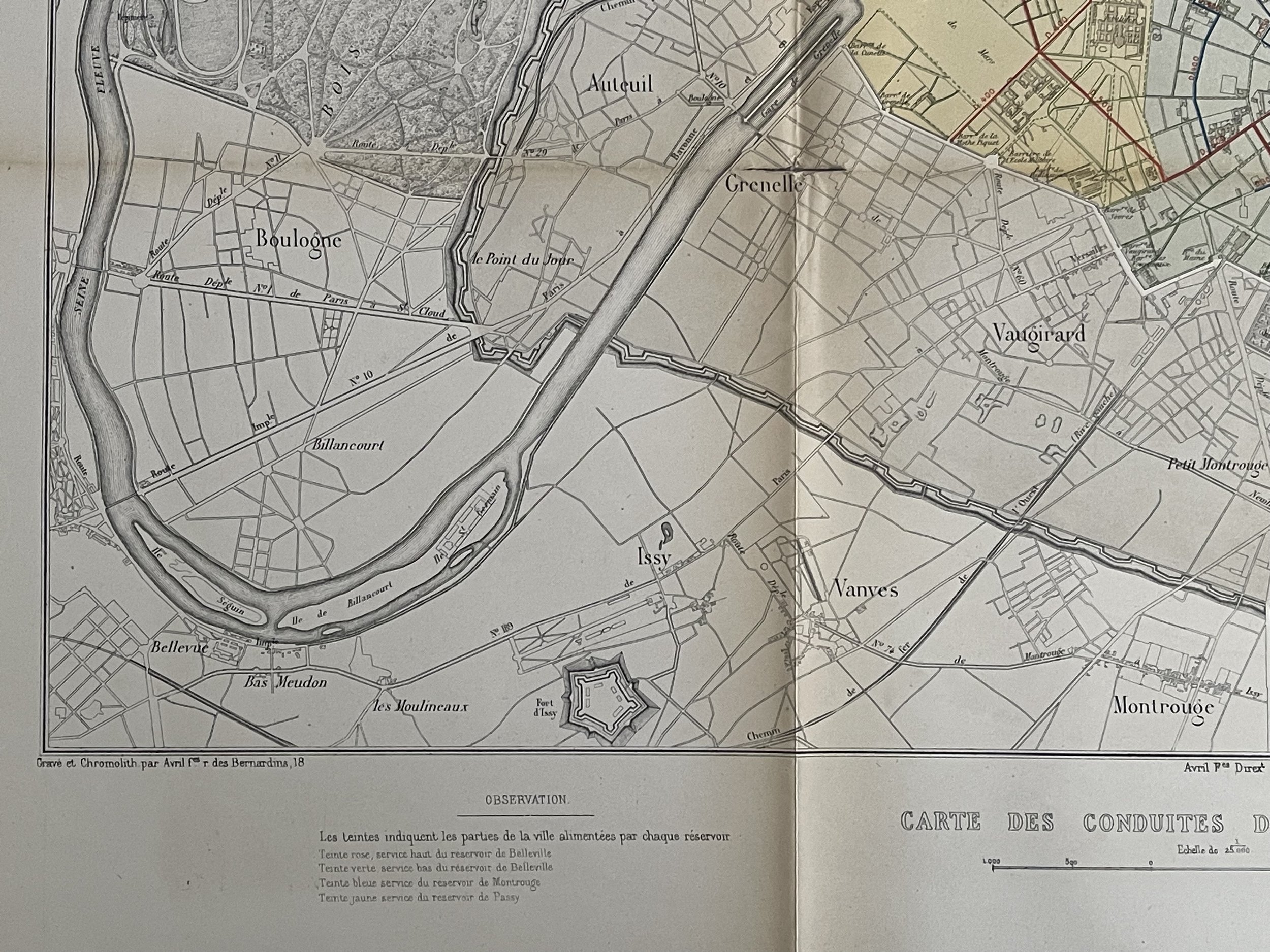

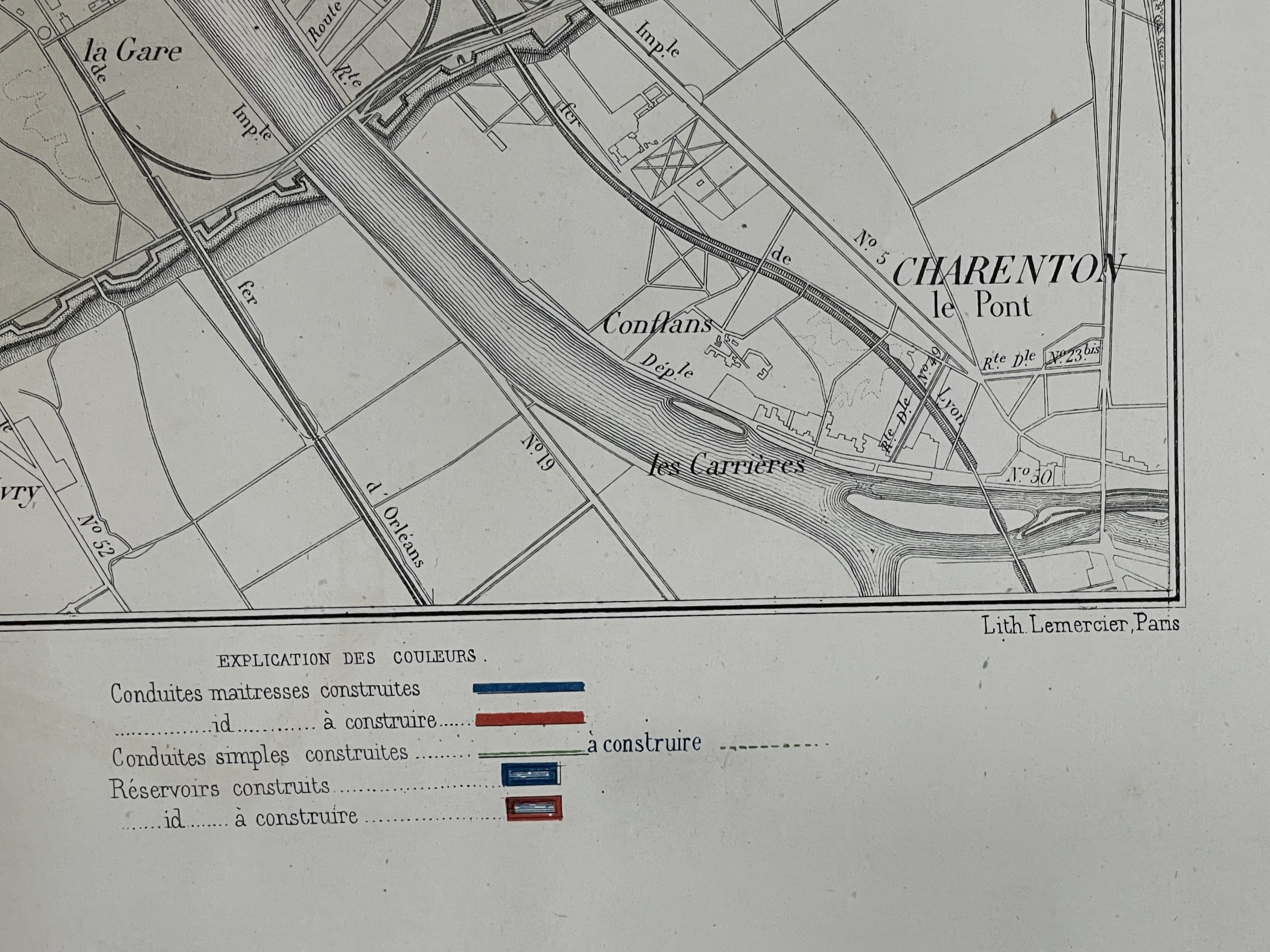

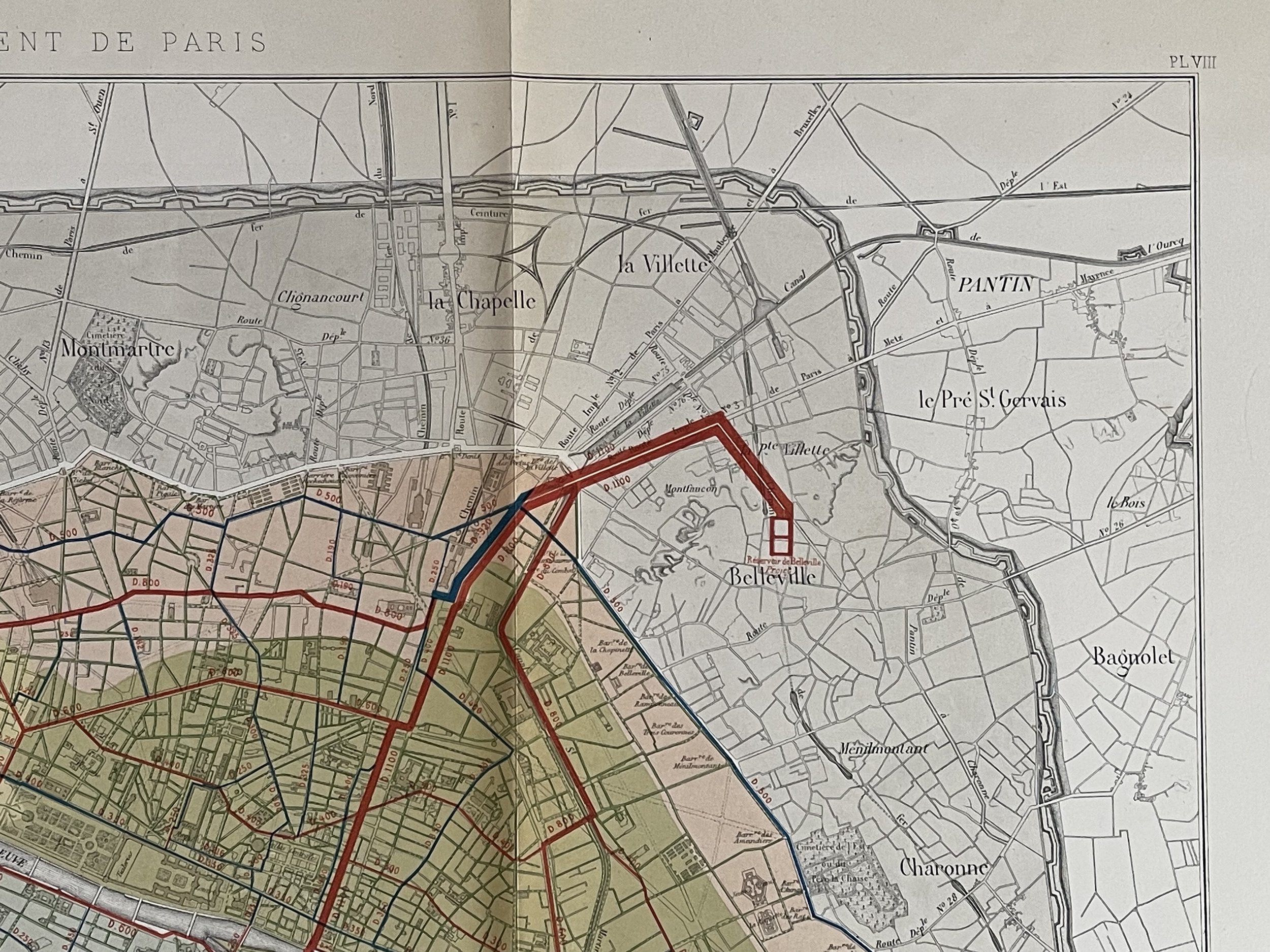

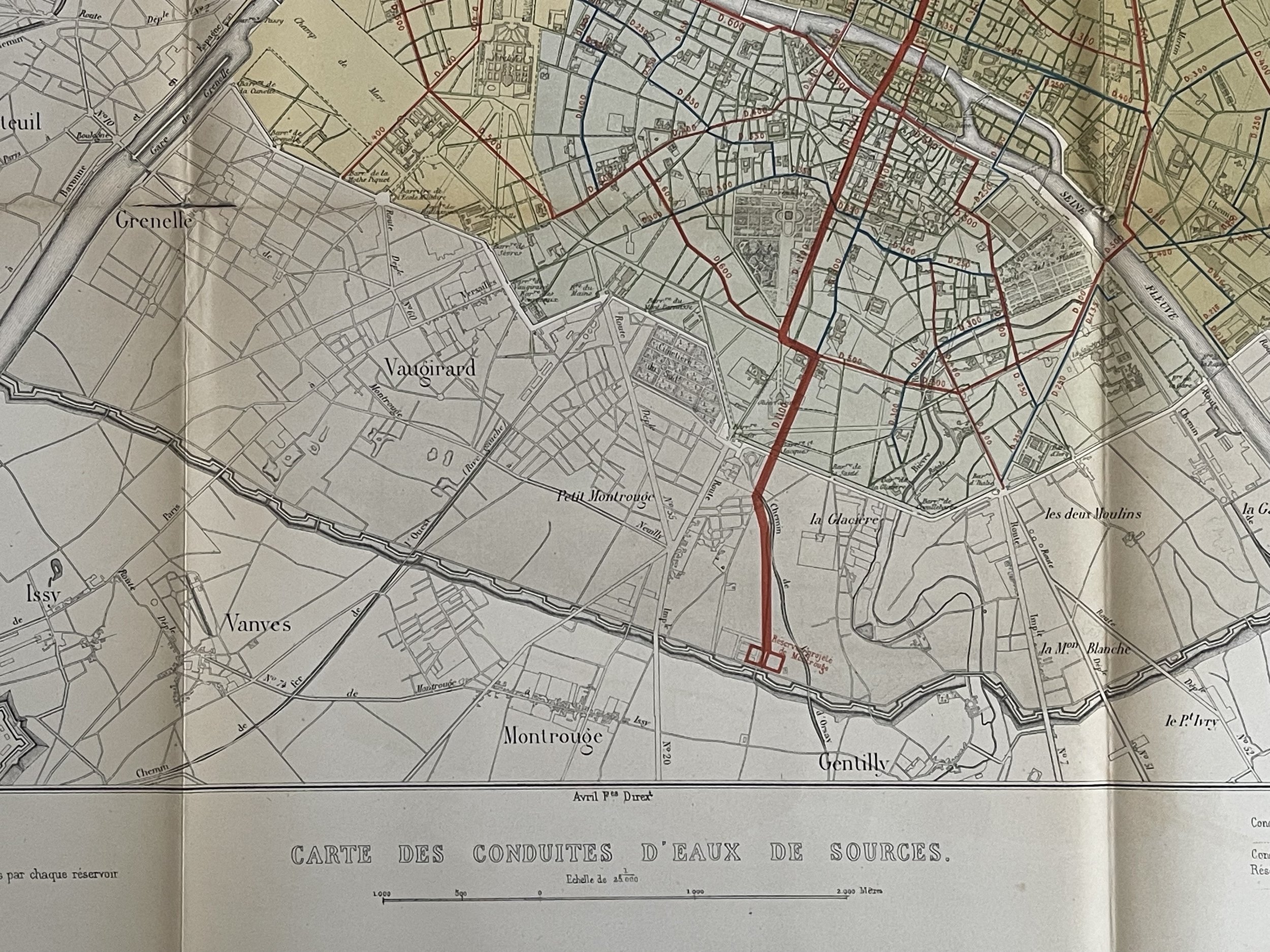

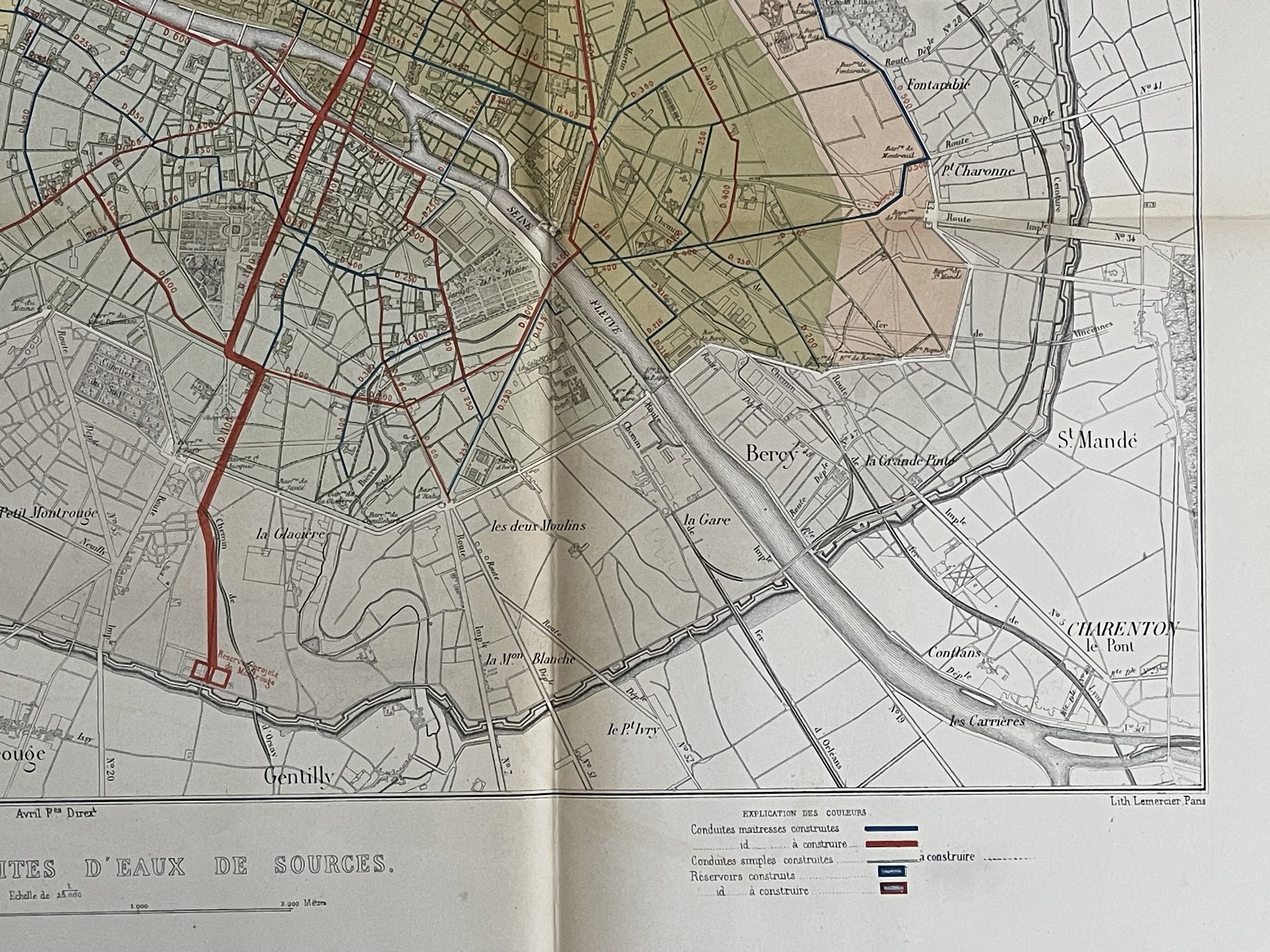

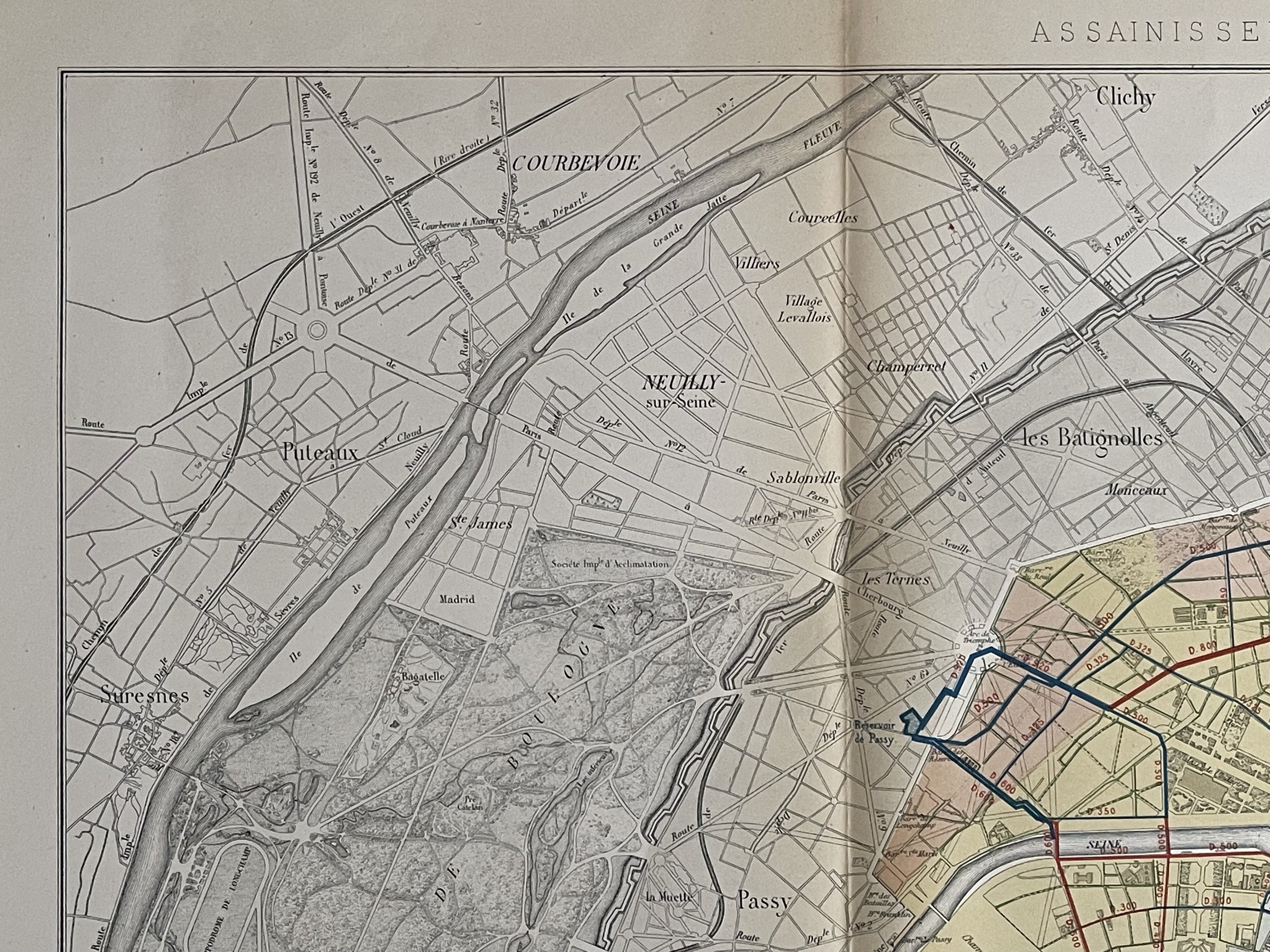

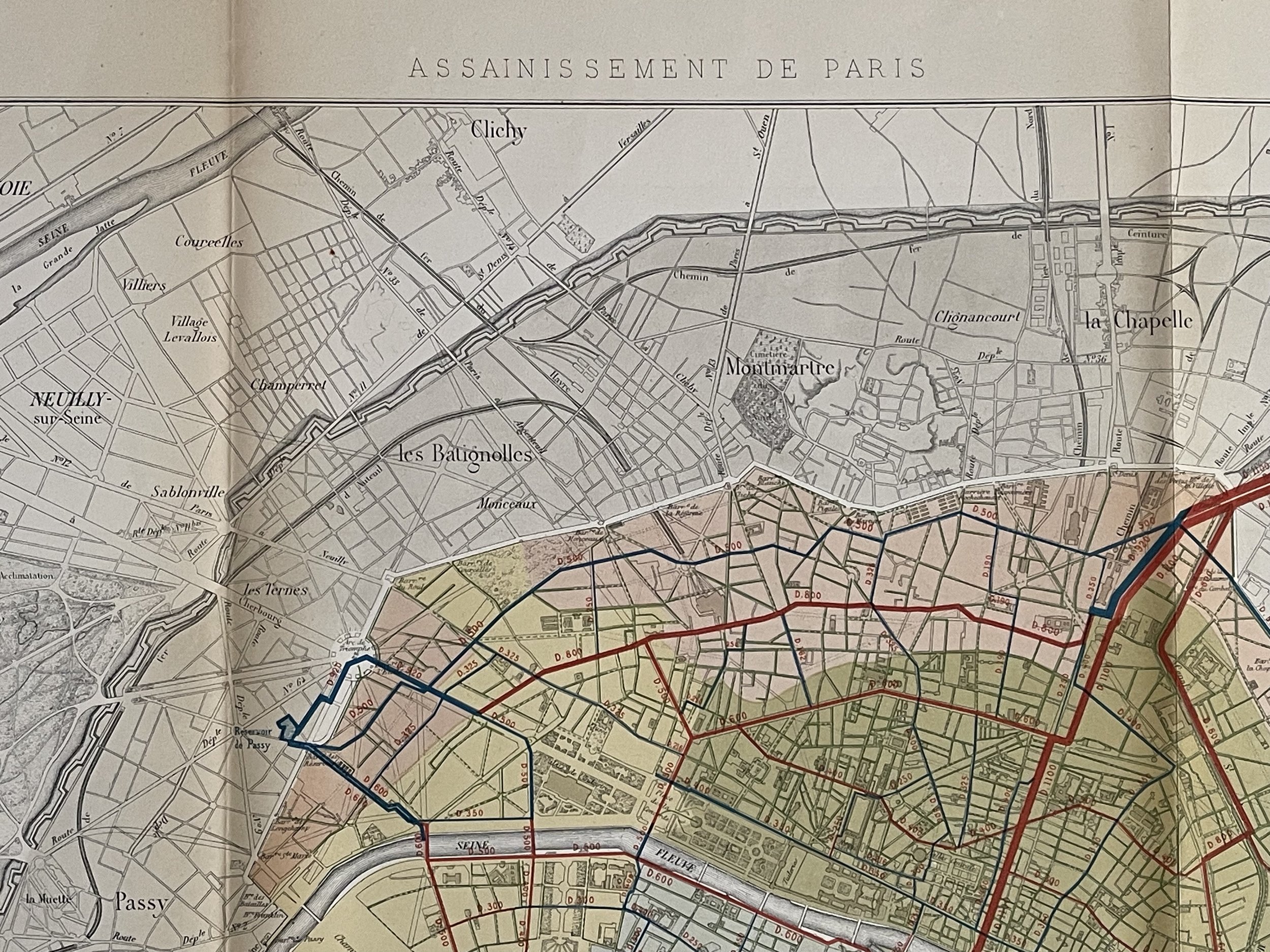

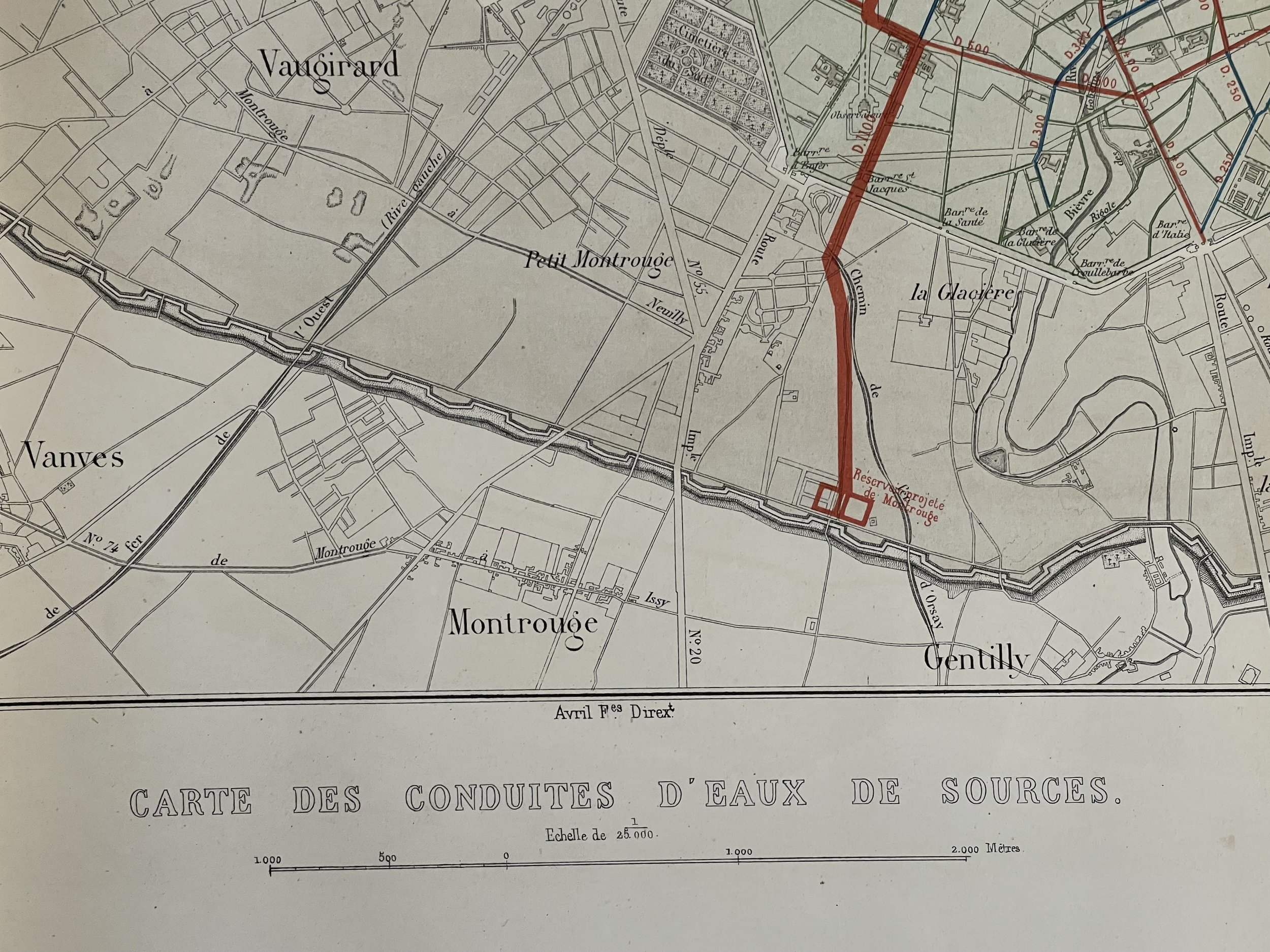

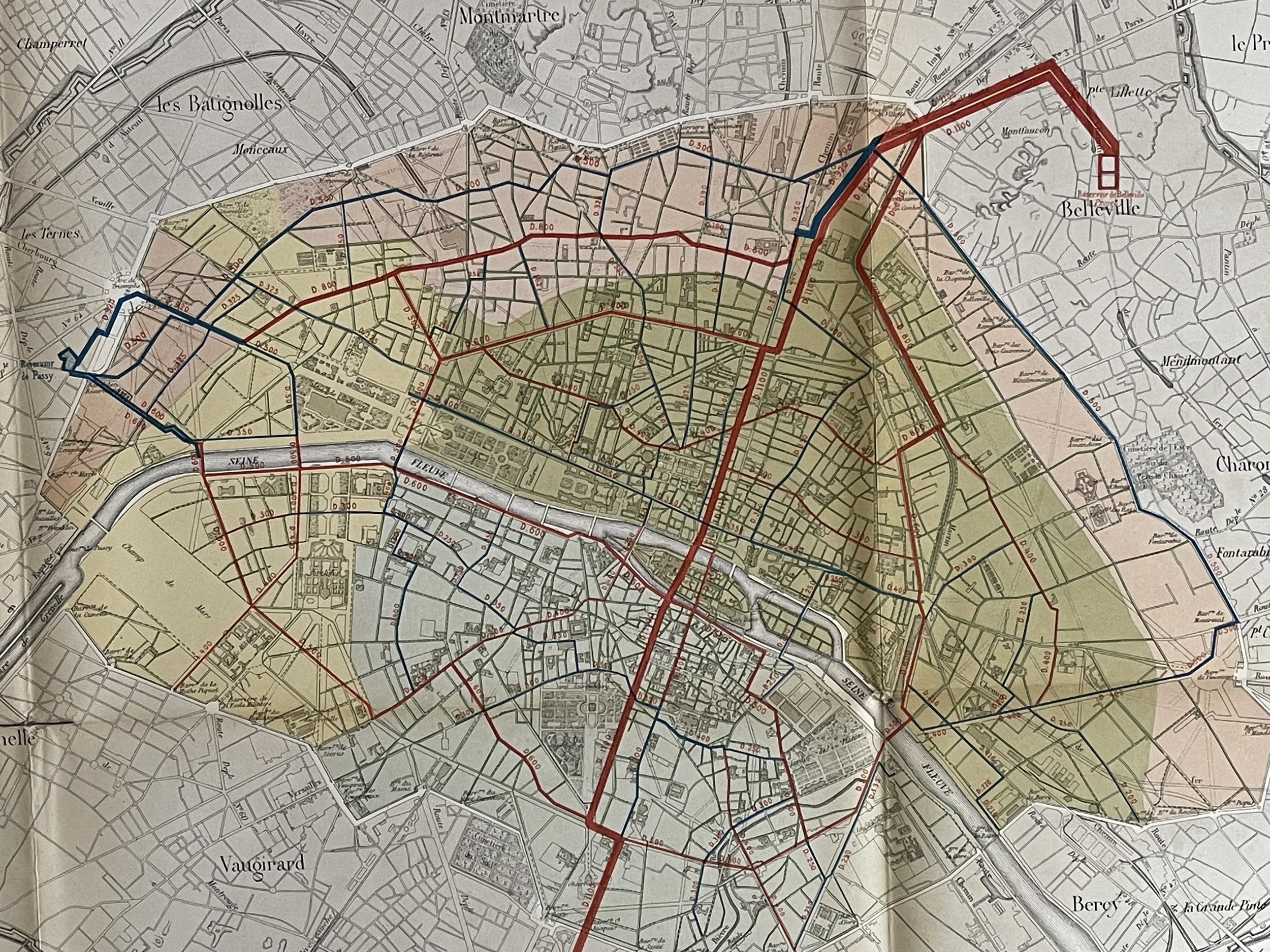

PARIS carte des conduites d'eaux de sources - WATER SPRINGS and SANITATION - Lemercier, Rose-Joseph - 1858

The water supply at the end of the 19th century in Paris was marked by their separation according to quality.

Eugène Belgrand's plan, a formidable turning point in Parisian water managementWater supply at the end of the 19th century

From 1854, the water supply was completely redesigned . This was the main project of engineer Eugène Belgrand.

Until then, the same water supplied homes but also factories and gardens. He decided to separate the origins of the waters according to the destinations. So, in 1854, the city of Paris was supplied as follows (in m 3 per day): The engineer Eugène Belgrand proposed that river water (of poor quality) be allocated to industrial needs, watering and domestic needs.

For their part, spring water, that transported by the Arcueil aqueduct, could be dedicated to domestic use. However, the initial flow was not sufficient. It was therefore necessary to capture new sources to increase their capacity to 122,000 m3 .

Thus, good quality water could be brought to 500,000 Parisians . We were still far from feeding the 2 million Parisians at the time. Due to the size of the city of Paris and the difficulty of obtaining water during the hot season, it was supplemented with water taken from the Seine at Maisons Alfort. It was then advised to filter the water well before drinking it.

The water distribution network at the end of the 19th century supplied the neighbourhoods... if they had sewers!

Ponds and reservoirs

To guarantee sufficient pressure for the different districts of Paris, water is raised in Paris in certain basins and reservoirs . This accumulation also made it possible to partially compensate for irregularities in water supply. They were also used in case of fire by firefighters.

Thus, at the end of the 19th century, the city had 18 basins:

8 were fed by the waters of the Ourcq ,

5 by the waters of the Seine,

1 by the waters of the Ourcq and Belleville ,

2 by the waters of the Seine, Arcueil and the Grenelle well.

As a result, this system resulted in a certain mixture of some origins, while seeking to respect a certain healthiness. These basins were constructed of sheet metal or masonry. To guarantee their solidity, they were divided into several compartments. The bottom and surrounding walls were made of concrete . Some were installed in cascade to receive distributed water that had not been used on a lower floor.

The pipes

At the end of the 19th century, Paris already had a vast pipeline network On the right bank, the large pipes followed the route of the old Fermiers Générals wall, approximately the route of line 2 of the metro. Overall, the starting points in Paris were the basins of Ménilmontant, Montrouge, Gentilly, la Villette.

Downstream of these pipes, several secondary pipes were attached to supply the fountains and especially the houses.

However, the network was not sufficient then . The municipal authorities then wanted to monitor the progress of the sewers . In fact, they wanted to manage evacuations to preserve the integrity of neighborhoods. Large leaks can seriously damage roadways and threaten buildings. The Parisian pipes of the large pipelines were made of cast iron . It was indeed a question of being able to withstand great pressures. Built as 2 meter modules, they were most often placed in sewers. In some cases, they were installed in trenches 1.5 meters deep. To join them, road workers held tarred ropes. Smaller pipes were very often made of lead .

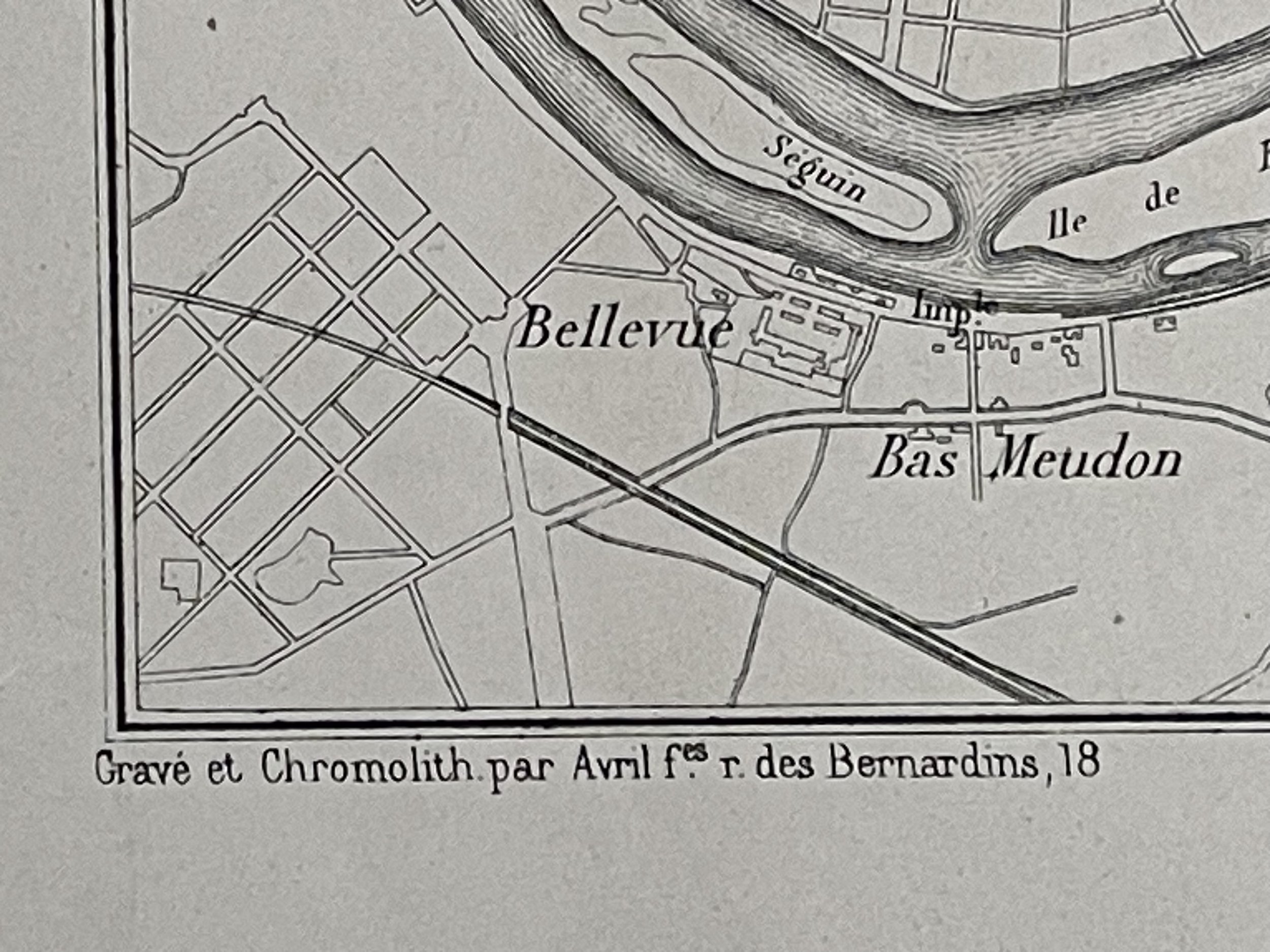

Lithographer / Engraver - Lemercier, Rose-Joseph (June 29, 1803 - 1887)

Rose-Joseph Lemercier (June 29, 1803 - 1887) was a French photographer, lithographer, and printer. One of the most important Parisian lithographers of the 19th century, Lemercier was born in Paris into a family of seventeen children. His father was a basket maker, and he even began working as a basket maker at the age of fif-teen, but Lemercier was drawn to lithography and printing and soon entered into an apprenticeship with Langlumé, where he worked from 1822 until 1825. After working for a handful of other printers, Lemercier started his own firm in 1828 at 2, rue Pierre Sarrazin with only one printing press. He subsequently moved a few more times before arriving at 57, rue de Seine, where he founded the printing firm Lemercier and Company. Lemercier created the firm Lemercier, Bénard and Company in 1837 with Jean François Bénard.

Lemercier bought out Bénard's share in the firm in 1843 and, since his two sons died at a young age, he decided to bring his nephew Alfred into the business beginning in 1862, who would progressively take on more and more responsibility in running the firm. Between 1850 and 1870, Lemercier's firm was the largest lithographic company in Paris. The firm began to decline in prestige in the early 1870s, and, after Lemercier's death in 1887, its descent only quickened. It is unclear when the firm closed, but Alfred directed the firm until his death in 1901.

Has a little damage at the fold junctions and on the edge. Pricing and grading commensurate.

The water supply at the end of the 19th century in Paris was marked by their separation according to quality.

Eugène Belgrand's plan, a formidable turning point in Parisian water managementWater supply at the end of the 19th century

From 1854, the water supply was completely redesigned . This was the main project of engineer Eugène Belgrand.

Until then, the same water supplied homes but also factories and gardens. He decided to separate the origins of the waters according to the destinations. So, in 1854, the city of Paris was supplied as follows (in m 3 per day): The engineer Eugène Belgrand proposed that river water (of poor quality) be allocated to industrial needs, watering and domestic needs.

For their part, spring water, that transported by the Arcueil aqueduct, could be dedicated to domestic use. However, the initial flow was not sufficient. It was therefore necessary to capture new sources to increase their capacity to 122,000 m3 .

Thus, good quality water could be brought to 500,000 Parisians . We were still far from feeding the 2 million Parisians at the time. Due to the size of the city of Paris and the difficulty of obtaining water during the hot season, it was supplemented with water taken from the Seine at Maisons Alfort. It was then advised to filter the water well before drinking it.

The water distribution network at the end of the 19th century supplied the neighbourhoods... if they had sewers!

Ponds and reservoirs

To guarantee sufficient pressure for the different districts of Paris, water is raised in Paris in certain basins and reservoirs . This accumulation also made it possible to partially compensate for irregularities in water supply. They were also used in case of fire by firefighters.

Thus, at the end of the 19th century, the city had 18 basins:

8 were fed by the waters of the Ourcq ,

5 by the waters of the Seine,

1 by the waters of the Ourcq and Belleville ,

2 by the waters of the Seine, Arcueil and the Grenelle well.

As a result, this system resulted in a certain mixture of some origins, while seeking to respect a certain healthiness. These basins were constructed of sheet metal or masonry. To guarantee their solidity, they were divided into several compartments. The bottom and surrounding walls were made of concrete . Some were installed in cascade to receive distributed water that had not been used on a lower floor.

The pipes

At the end of the 19th century, Paris already had a vast pipeline network On the right bank, the large pipes followed the route of the old Fermiers Générals wall, approximately the route of line 2 of the metro. Overall, the starting points in Paris were the basins of Ménilmontant, Montrouge, Gentilly, la Villette.

Downstream of these pipes, several secondary pipes were attached to supply the fountains and especially the houses.

However, the network was not sufficient then . The municipal authorities then wanted to monitor the progress of the sewers . In fact, they wanted to manage evacuations to preserve the integrity of neighborhoods. Large leaks can seriously damage roadways and threaten buildings. The Parisian pipes of the large pipelines were made of cast iron . It was indeed a question of being able to withstand great pressures. Built as 2 meter modules, they were most often placed in sewers. In some cases, they were installed in trenches 1.5 meters deep. To join them, road workers held tarred ropes. Smaller pipes were very often made of lead .

Lithographer / Engraver - Lemercier, Rose-Joseph (June 29, 1803 - 1887)

Rose-Joseph Lemercier (June 29, 1803 - 1887) was a French photographer, lithographer, and printer. One of the most important Parisian lithographers of the 19th century, Lemercier was born in Paris into a family of seventeen children. His father was a basket maker, and he even began working as a basket maker at the age of fif-teen, but Lemercier was drawn to lithography and printing and soon entered into an apprenticeship with Langlumé, where he worked from 1822 until 1825. After working for a handful of other printers, Lemercier started his own firm in 1828 at 2, rue Pierre Sarrazin with only one printing press. He subsequently moved a few more times before arriving at 57, rue de Seine, where he founded the printing firm Lemercier and Company. Lemercier created the firm Lemercier, Bénard and Company in 1837 with Jean François Bénard.

Lemercier bought out Bénard's share in the firm in 1843 and, since his two sons died at a young age, he decided to bring his nephew Alfred into the business beginning in 1862, who would progressively take on more and more responsibility in running the firm. Between 1850 and 1870, Lemercier's firm was the largest lithographic company in Paris. The firm began to decline in prestige in the early 1870s, and, after Lemercier's death in 1887, its descent only quickened. It is unclear when the firm closed, but Alfred directed the firm until his death in 1901.

Has a little damage at the fold junctions and on the edge. Pricing and grading commensurate.

The water supply at the end of the 19th century in Paris was marked by their separation according to quality.

Eugène Belgrand's plan, a formidable turning point in Parisian water managementWater supply at the end of the 19th century

From 1854, the water supply was completely redesigned . This was the main project of engineer Eugène Belgrand.

Until then, the same water supplied homes but also factories and gardens. He decided to separate the origins of the waters according to the destinations. So, in 1854, the city of Paris was supplied as follows (in m 3 per day): The engineer Eugène Belgrand proposed that river water (of poor quality) be allocated to industrial needs, watering and domestic needs.

For their part, spring water, that transported by the Arcueil aqueduct, could be dedicated to domestic use. However, the initial flow was not sufficient. It was therefore necessary to capture new sources to increase their capacity to 122,000 m3 .

Thus, good quality water could be brought to 500,000 Parisians . We were still far from feeding the 2 million Parisians at the time. Due to the size of the city of Paris and the difficulty of obtaining water during the hot season, it was supplemented with water taken from the Seine at Maisons Alfort. It was then advised to filter the water well before drinking it.

The water distribution network at the end of the 19th century supplied the neighbourhoods... if they had sewers!

Ponds and reservoirs

To guarantee sufficient pressure for the different districts of Paris, water is raised in Paris in certain basins and reservoirs . This accumulation also made it possible to partially compensate for irregularities in water supply. They were also used in case of fire by firefighters.

Thus, at the end of the 19th century, the city had 18 basins:

8 were fed by the waters of the Ourcq ,

5 by the waters of the Seine,

1 by the waters of the Ourcq and Belleville ,

2 by the waters of the Seine, Arcueil and the Grenelle well.

As a result, this system resulted in a certain mixture of some origins, while seeking to respect a certain healthiness. These basins were constructed of sheet metal or masonry. To guarantee their solidity, they were divided into several compartments. The bottom and surrounding walls were made of concrete . Some were installed in cascade to receive distributed water that had not been used on a lower floor.

The pipes

At the end of the 19th century, Paris already had a vast pipeline network On the right bank, the large pipes followed the route of the old Fermiers Générals wall, approximately the route of line 2 of the metro. Overall, the starting points in Paris were the basins of Ménilmontant, Montrouge, Gentilly, la Villette.

Downstream of these pipes, several secondary pipes were attached to supply the fountains and especially the houses.

However, the network was not sufficient then . The municipal authorities then wanted to monitor the progress of the sewers . In fact, they wanted to manage evacuations to preserve the integrity of neighborhoods. Large leaks can seriously damage roadways and threaten buildings. The Parisian pipes of the large pipelines were made of cast iron . It was indeed a question of being able to withstand great pressures. Built as 2 meter modules, they were most often placed in sewers. In some cases, they were installed in trenches 1.5 meters deep. To join them, road workers held tarred ropes. Smaller pipes were very often made of lead .

Lithographer / Engraver - Lemercier, Rose-Joseph (June 29, 1803 - 1887)

Rose-Joseph Lemercier (June 29, 1803 - 1887) was a French photographer, lithographer, and printer. One of the most important Parisian lithographers of the 19th century, Lemercier was born in Paris into a family of seventeen children. His father was a basket maker, and he even began working as a basket maker at the age of fif-teen, but Lemercier was drawn to lithography and printing and soon entered into an apprenticeship with Langlumé, where he worked from 1822 until 1825. After working for a handful of other printers, Lemercier started his own firm in 1828 at 2, rue Pierre Sarrazin with only one printing press. He subsequently moved a few more times before arriving at 57, rue de Seine, where he founded the printing firm Lemercier and Company. Lemercier created the firm Lemercier, Bénard and Company in 1837 with Jean François Bénard.

Lemercier bought out Bénard's share in the firm in 1843 and, since his two sons died at a young age, he decided to bring his nephew Alfred into the business beginning in 1862, who would progressively take on more and more responsibility in running the firm. Between 1850 and 1870, Lemercier's firm was the largest lithographic company in Paris. The firm began to decline in prestige in the early 1870s, and, after Lemercier's death in 1887, its descent only quickened. It is unclear when the firm closed, but Alfred directed the firm until his death in 1901.

Has a little damage at the fold junctions and on the edge. Pricing and grading commensurate.

Code : A844

Cartographer : Cartographer / Engraver / Publisher: Lemercier, Rose-Joseph

Date : Publication Place / Date - Circa 1858

Size : Sheet size: Image Size: 68 x 55 cm

Availability : Available

Type - Genuine - Antique

Grading A-

Where Applicable - Folds as issued. Light box photo shows the folio leaf centre margin hinge ‘glue’, this is not visible otherwise.

Tracked postage, in casement. Please contact me for postal quotation outside of the UK.